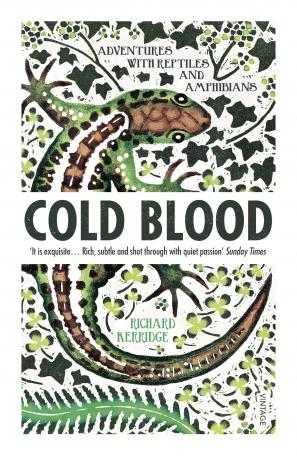

Richard Kerridge's Cold Blood

- Anthony Nanson

- Jun 4, 2016

- 2 min read

Updated: Feb 6

There are not too many dinosaurs in Britain today, unless you count the birds. And as a kid with my animal books I was underwhelmed by the slender list of living reptiles this country boasts: three kinds of snake and three kinds of (small) lizard. One of the many accomplishments of Richard Kerridge’s memoir Cold Blood is to evoke a sense of specialness about these humble species – plus the native species of amphibians – and their presence in the wild around us.

British nature writing is booming right now. Cold Blood is an exquisitely written and innovative contribution to the genre. It’s basically a boyhood memoir, whose central narrative arc concerns the author’s relationship with his father, presented as subtly interconnected with his all-absorbing hobby of collecting reptiles and amphibians for a miniature zoo in the garden.

What impressed me most about this book was the way it aroused in me a web of delicate and diverse nuances of feeling. Maybe the strongest of these was nostalgia: not precisely for my own boyhood, but for something just out of reach of my memory, an English boyhood running about a decade before mine. Some of the cultural references were familiar but slightly time-lagged. For example, Kerridge refers to particular series of tea-packet cards that I was aware of as having preceded the later series that I collected. More significantly, his freedom to wander off in the countryside was that bit greater than I experienced, a step closer to the immense outdoor freedom I envied my own father having enjoyed; a freedom that has been all but obliterated in my nephews’ generation.

Meanwhile the hobby of capturing wild animals, which initiated Kerridge’s lifelong commitment to ecological concerns, has become more or less outlawed for the sake of the species’ survival. A particularly poignant moment of irony is when we see the adult Kerridge using skills he learnt as a boy, to capture animals in the hand, as he participates in conservation work. The moment makes concrete the story emerging through the book that creatures that were once just there, part of the landscape, have become rarer, more restricted in range, their existence fragile.

In this way the importance of the conservation themes Kerridge cares about creeps up out of those nuances of feeling his writing evokes. He never rants about it. Sometimes he slips in some facts and figures. Sometimes he invites imaginative identification with the perspective of, say, a toad in the moments before it gets flattened by a truck. But it’s his own generously personal story that draws you in – that and an extremely accessible style. Cold Blood squares the circle of being a sophisticated and ecologically committed piece of literature and at the same time an easy, engaging read for anyone who in the past would have enjoyed the likes of Cider with Rosie and My Family and Other Animals.

Comments