Researching Deep Time was an excuse to rewatch the dinosaur films that had captivated me as boy. Through this painstaking scholarly process I discovered that in my memory two of these films had merged into one. That’s not entirely surprising because When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth is largely a remake of One Million Years B.C. Both centre on a romance that transcends the enmity between the barbaric ‘Rock People’ and more hippy ‘Shell People’.

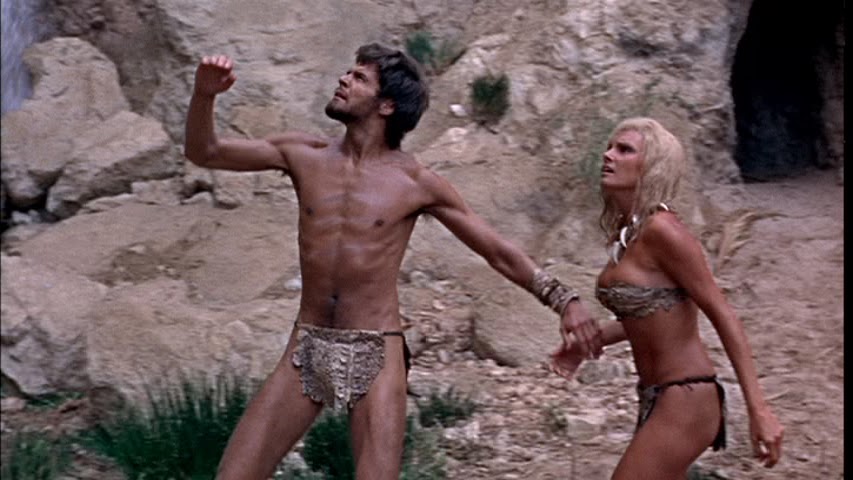

Of the two, One Million Years B.C. has the better reputation, largely because of the mesmerising presence of Raquel Welch, though John Richardson is a good actor too, and Harryhausen’s stop-motion dinosaurs are superb. When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth has dinosaurs animated by Jim Danforth which are just as good. It also boasts a more complex plot. The hero saves the heroine after her people have tried to sacrifice her (for being blonde), so the Rock People are after them; but he already has a woman back among the Shell People, so she’s not best pleased and the Shell People end up equally hostile to the happy couple. The film’s problem is that the actors are upstaged by the dinosaurs. Victoria Vetri is manifestly a glamour model who can’t really act. Robin Hawdon is so unresponsive to all the dramas he’s engulfed in that either he can’t act either or he’s pursuing a commitment to deadpan irony. Both of them are so skinny in physique – which their prehistoric outfits do little to conceal – that’s it hard to believe either of them would last long amidst the rigours of the Palaeolithic.

Hammer must have been playing the film for laughs, though. The drama of the sacrifice scene is wonderfully undermined by the guys at the back playing a tonk-tonk-tonk percussion number with drumsticks on skulls. And then there’s the astonishing ‘prehistoric dance’, unlike anything you’ve ever seen, performed by the jealous other woman – the much more charismatic Imogen Hassall. And the protracted battle with a gigantic plesiosaur that’s managed to lurch far enough up the beach on its flippers to devastate the Shell People’s camp. And the cuteness of the mother dinosaur who, upon finding Vetri asleep in a broken egg, is convinced she’s her offspring – and in consequence the woman can control the reptile when need arises.

The problem with that particular dinosaur is that, unlike the others, it looks nothing like any real kind of dinosaur. It reminds me of the reconstructions Richard Owen designed for the Great Exhibition of 1851, when no complete dinosaur skeletons had yet been found and so no one knew what they really looked like – except maybe the Native Americans, whose notions of a ‘Thunderbird’, inspired by dinosaur trackways, were closer to the truth. That’s nothing, you may say – of both this film and its predecessor – compared with the asynchronous juxtaposition of cavemen and dinosaurs, but these films are only reprising a trope established by Conan Doyle and Edgar Rice Burroughs, albeit without any rationale about an unusual compression of evolutionary processes.

The film prominently credits J.G. Ballard, who wrote a treatment for it at some stage. Ballard, poor man, thought When Dinosaurs Rule the Earth was terrible and tried to disown any connection with it, but of course Hammer wanted to make the most of his name. As for me, I retain great affection for this film. That four-note tune – da duh duh duh – that plays over and over again, the elemental dramas of storm, sea, and earthquake, the dinosaurs, the sweaty cavemen – and cavewomen – the bit where a pterosaur carries the hero off to its nest – the film had everything to electrify a prepubescent boy. I can remember how I felt watching it on TV sometime in the seventies, completely transported. And of course the child that you were lives on somewhere within you.

Bình luận